Australia

Those suffering from union corruption don’t care about politics

The Fight Against Corruption in the Construction Industry: A System in Crisis

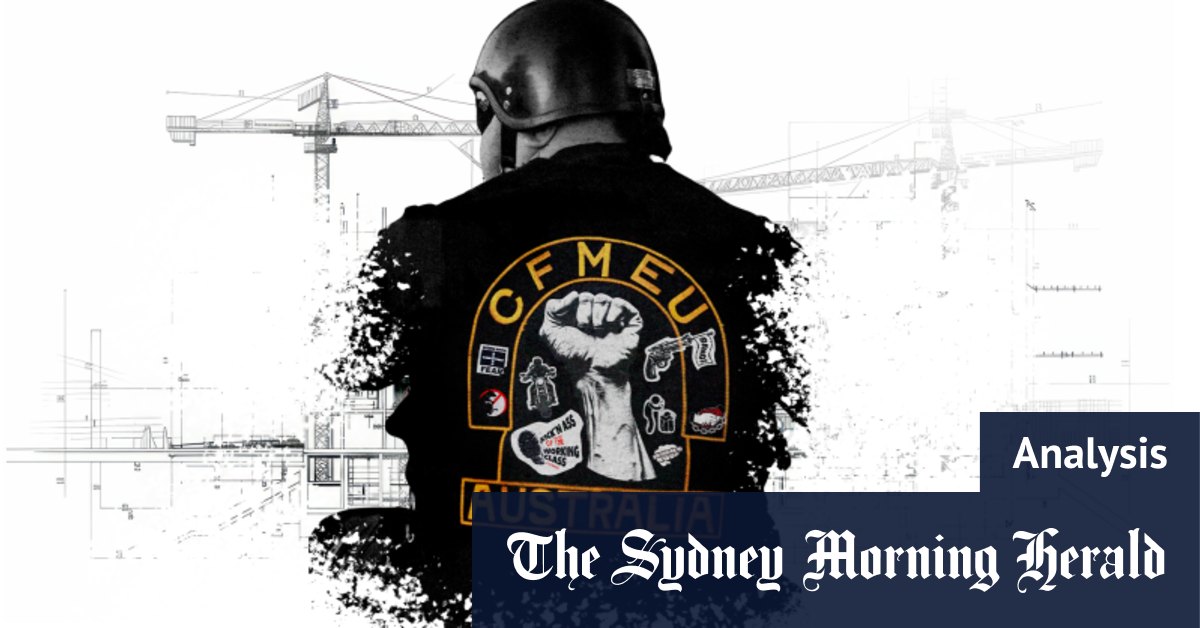

Corruption buster Geoffrey Watson, SC, has sounded the alarm on national television about the alarming state of corruption and organized crime in the construction industry. His revelations echo the concerns of many state and federal detectives who have privately conceded that the current strategies to combat crime and corruption in this sector are failing. Watson, appointed by the CFMEU’s administrator, Mark Irving, KC, has been investigating organized crime infiltration in the union and broader industry. His findings paint a grim picture: gangland figures, including bikies, are not only entrenched in the industry but are operating with relative impunity, particularly in Victoria’s taxpayer-funded Big Build projects and parts of NSW. This brazen criminal activity highlights the systemic failure of law enforcement and regulatory bodies to tackle the issue effectively.

The Limitations of Current Enforcement Efforts

Watson’s critique extends to Victoria Police, accusing them of inaction, and points out that even the Australian Federal Police (AFP) are hampered by a limited mandate. The raid on Gatto’s accountant last Thursday, part of an ongoing investigation with no charges laid, underscores the lack of progress. The question arises: if law enforcement agencies are unable to address the problem, how can a few courageous barristers like Watson and Irving hope to succeed? The answer, unfortunately, is they cannot. The current reliance on administrative or police action alone is insufficient to address the deeply entrenched corruption. The case of Derek Christopher, a former Victorian union boss under investigation for seven years without charges, exemplifies the systemic failure. Such delays send a clear message to wrongdoers: break the law, and you’ll likely get away with it.

The Need for Robust Legal Reforms

The limitations of the current system are further highlighted by the reluctance of victims to testify against intimidating figures like bikies and union thugs. Victorian Labor’s proposed anti-association laws may offer some hope but are easily circumvented and lack the necessary enforcement resources. A more comprehensive approach is needed, and Federal Opposition Leader Peter Dutton’s proposal of anti-racketeering laws warrants serious consideration. These laws have proven effective in the U.S. in dismantling mafia-linked rackets. However, as Watson notes, such laws require substantial enforcement resources, which are currently lacking. Additionally, the problem extends beyond unions, involving corrupt building companies and mobsters, making it a tripartite issue that demands a multifaceted solution.

The Case for a Targeted Commission of Inquiry

The deregistration of unions, as proposed by some, is a risky solution, as history shows it can drive corruption underground rather than eradicate it. Instead, what is needed is full accountability, which a well-targeted commission of inquiry could deliver. Victoria’s recent Wilson inquiry fell short, producing a superficial report that Watson rightly dismissed as a cover-up. The two previous royal commissions into the building industry (in 2001 and 2014) also failed to effect meaningful change, with the first glossing over organized crime and the second becoming mired in indiscriminate union-bashing. A searing, focused inquiry is long overdue to expose and address the rot in the construction sector.

Immediate Steps to Combat Corruption

In the short term, a major injection of funding into the administration is essential. Watson and Irving cannot tackle this crisis alone; they need a team of investigators and robust support. A properly funded federal-state taskforce with a legislated mandate beyond prosecution—encompassing deterrence and asset seizure—is critical. New laws targeting IR mediators like Gatto must also be introduced to rid the industry of such figures. State governments should blacklist companies linked to bikies, sending a strong message that such associations will not be tolerated. Without drastic reforms, the industry will continue to operate in a culture of fear and corruption.

A Call to Action for Meaningful Change

Watson’s rhetorical question on 60 Minutes—“Is this the sort of country anyone wants to live in?”—resonates deeply. The answer, of course, is no. The construction industry’s corruption crisis is not just about union thuggery or organized crime; it is about the failure of institutions to protect the public interest. Unless there is a collective commitment to serious reforms—legislative, investigative, and cultural—the status quo will persist. The fight against corruption in the building industry is not just about cleaning up a sector; it is about reclaiming a country’s integrity. As Watson and Irving’s efforts show, courage and determination are essential, but they must be matched by systemic change. The time for action is now.

-

Politics4 days ago

Politics4 days agoWhite House video rips Senate Dems with their own words for ‘hypocrisy’ over looming shutdown

-

Canada4 days ago

Canada4 days agoCanada’s Wonderland scrapping popular 20-year rollercoaster ahead of 2025 season

-

Lifestyle4 days ago

Lifestyle4 days ago2025 Mercury retrograde in Aries and Pisces: How to survive and thrive

-

World5 days ago

World5 days agoOregon mental health advisory board includes member who identifies as terrapin species

-

Tech2 days ago

Tech2 days agoBest Wireless Home Security Cameras of 2025

-

Tech2 days ago

Tech2 days agoFrance vs. Scotland: How to Watch 2025 Six Nations Rugby Live From Anywhere

-

Politics4 days ago

Politics4 days agoTrump admin cracks down on groups tied to Iran targeting US citizens, sanctions Iranian-linked Swedish gang

-

Tech1 day ago

Tech1 day agoHow to Watch ‘American Idol’ 2025: Stream Season 23